By Dr Christine Jones

Organic carbon is the basic building block for all life on – and in – the earth. We cannot live without it. Neither can our soils.

Historical Loses of Soil & Soil Carbon

In little over 200 years of European settlement, more than 70 percent of Australian agricultural land has become seriously degraded.

The world’s soils hold three times as much carbon as the at- mosphere and over four times as much carbon as the vegeta- tion. With 82% of terrestrial carbon in soil (compared to only 18% in vegetation), soil represents the largest carbon sink over which we have control. Soil is also the world’s largest store of terrestrial diversity, with over 95% of life forms being underground (that is, only 5% of biodiversity is above ground). The most meaningful indicator for the health of the land,

and the long-term wealth of a nation, is whether soil is being formed or lost. If soil is being lost, so too is the economic and ecological foundation on which production and conservation are based.

“A 0.5% increase in soil carbon on 2% of agricultural land will sequester all Australia’s CO2 emissions ”

On average, 7 tonnes of topsoil is lost for every tonne of grain produced. In addition to the loss of soil itself, there has been a reduction of between 50% and 80% in the organic carbon content of surface soils in Australia since European settle- ment.

Losses of carbon of this magnitude have immeasurable economic and environmental implications. Soil carbon is the prime determinant of agricultural productivity, landscape function and water quality.

The carbon and water cycles are intrinsically linked. Humus holds approximately four times its own weight in water. The most beneficial adaptation strategy for climate change would therefore be one that focuses on increasing the levels of both carbon and water in soils.

Building New Topsoil

The essential first step to rebuilding topsoil is to maximise photosynthetic capacity. A permanent cover of perennial plants provides an ongoing source of soluble carbon for the soil ecosystem, buffers soil temperatures, inhibits weeds, reduces erosion, improves porosity, enhances aggregate stability and water infiltration, slows evaporation and ‘condi- tions’ the soil.

Sequestering humified carbon in soils represents a practical, permanent and productive solution to removing excess CO2 from the atmosphere. By adopting regenerative soil-building practices, it is practical, possible and profitable for broadacre cropping and grazing enterprises to record a net sequestra- tion of carbon in the order of 25 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of product sold (after emissions accounted for).

It would require only a 0.5% increase in soil carbon on 2% of agricultural land to sequester all Australia’s emissions of carbon dioxide. That is, the annual emissions from all indus- trial, urban and transport sources could be sequestered in farmland soils if incentive was provided to landholders for this to happen.

Farming & Health

The best national health policy is good agricultural policy. In reality, the farming sector sits at the centre of a complex, capital intensive supply chain focussed largely on production. Decisions are based on the cost of inputs and the anticipated value of outputs. Rarely is the nutritional value of the product considered. The health dimension has tended be viewed as a technical problem that can be fixed by pharmacological magic bullets.

Interestingly, when people are asked which factors are of greatest importance to them personally, good health nearly always tops the list. Contrary to popular belief, good health is not determined by the quality of our medical system. Rather, it is closely linked to the nutrient content of food – which in turn is linked to the ecological health and organic carbon content of the soil in which food is grown.

Routine premature deaths by degenerative conditions such as cardiovascular disease and cancer have become prominent when they were once relatively uncommon. The cancer rate, for example, has increased from approximately 1 in 100, fifty years ago, to almost 1 in 2 today.

Livestock & Methane

Wetlands, rivers, oceans, lakes, plants, decaying vegetation (especially in moist environments such as rainforests) – and a wide variety of creatures great and small, have been produc- ing methane for millions of years. A clear distinction needs

to be made between natural methane from ruminants and man-made methane from industrial sources. For example,

a medium-sized whale produces methane emissions equiva- lent to 40 cows. There are international policies in place to protect whales and other methane producing wildlife, as well as protecting and enhancing methane-producing ecosystems such as wetlands and rainforests. The natural methane pro- duced in the rumen of pasture fed livestock is not man-made – and is not increasing.

Global atmospheric levels of methane have remained relatively constant over the last ten years, despite increased ruminant numbers worldwide. This finding raises questions about the relative contribution of ruminant livestock to global methane levels and suggests that other sources and sinks may be playing a more significant role. The largest single source of methane worldwide is wetlands (22%), followed by coal, oil and natural gas (19%).

Mycorrhizal Fungi

Soil benefits in many ways from the presence of living plants year-round, due to reduced erosion, buffered temperatures, enhanced infiltration and markedly improved habitat for soil biota. Significantly, it is the photosynthetic capacity of living plants (rather than the amount of dead biomass added to soil) that is the driver for soil carbon accumulation.

The soluble carbon exuded into the rhizosphere by perennial groundcover plants and transported deep into soil by mycor- rhizal fungi, provides energy for the vast array of microbes and soil invertebrates that produce sticky substances enabling soil particles to be glued together into lumps (ag- gregates). When soil is well aggregated, the spaces (pores) between the aggregates allow the soil to breathe, as well as absorb moisture quickly when it rains. A healthy topsoil should be ‘more space than stuff’, that is, less than 50% solid materi- als and more than 50% spaces.

Conclusion

The longer we delay undertaking changes to land manage- ment, the more soil (and soil carbon and soil water) will be lost, exposing an increasingly fragile agricultural sector to escalating production risks, rising input costs and vulnerability to climatic extremes.

For more information visit Dr Christine Jones’ website, Amaz- ing Carbon – www.amazingcarbon.com.

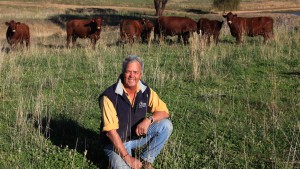

“Yamburgan cattle are cattle that com- bine performance and docility and are sought after by both lot feeders and grass finishers who consistently comment on the high percentage of the cattle that meet the highest specifications.”

“Yamburgan cattle are cattle that com- bine performance and docility and are sought after by both lot feeders and grass finishers who consistently comment on the high percentage of the cattle that meet the highest specifications.”